- Title

-

Telomerase Depletion Accelerates Ageing of the Zebrafish Brain

- Authors

- Martins, R.R., Besse, S., Ellis, P.S., Sevil, R., Hartopp, N., Purse, C., Everett-Brown, G., Evans, O., Mughal, N., Wahib, M.H.F., Yazigan, Z., Morsli, S., Jimenez-Gonzalez, A., Grierson, A., Mortiboys, H., Hammond, C., Rera, M., Henriques, C.M.

- Source

- Full text @ Aging Cell

|

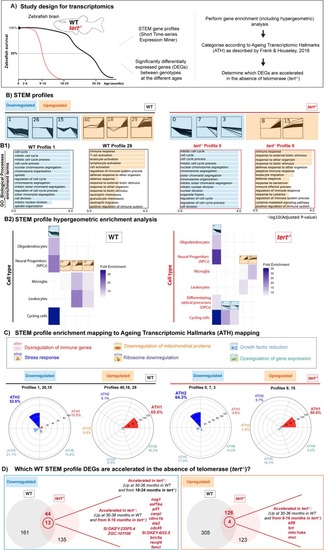

Transcriptomic signatures of ageing in the presence and absence of telomerase in the zebrafish brain. (A) Schematic figure of the study design for transcriptomics: RNA from whole brain tissue from young (2–6 months), young adult (9–16 months), middle aged (18–24 months) and old, (30–36 months) WT fish, and young (2–6 months), middle aged (9–16 months) and old (18–24 months) |

|

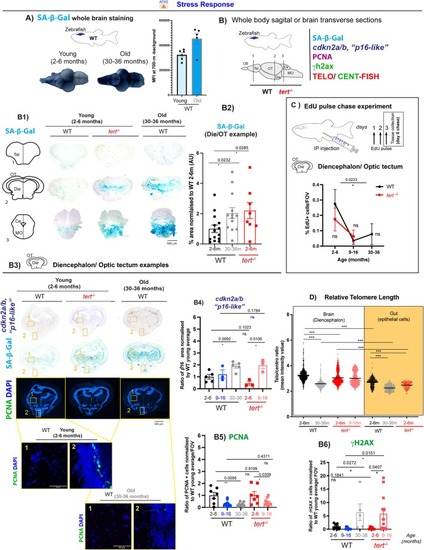

Telomerase (tert) depletion accelerates ageing‐associated stress response in the zebrafish brain. Brain tissue collected from 2–6 months, 9–16 months and 30–36 months WT fish, and 2–6 months and 9–16 months |

|

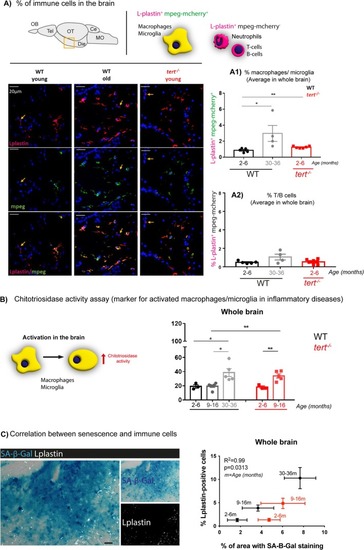

Telomerase depletion is associated with increased inflammation in the aged zebrafish brain. (A) Representative images of mpeg‐mcherry and L‐plastin staining in the diencephalon of adult zebrafish (schematic figure highlights the region imaged as diencephalon). The yellow arrows highlight Lplastin+; mpeg− cells. (A1) Quantifications of L‐plastin‐positive; mpeg‐positive cells (orange; from red and green co‐localisation) and (A2) L‐plastin‐positive; mpeg‐negative cells (red) in the whole zebrafish brain show an increased number of macrophages/microglia (L‐plastin‐positive; mpeg‐positive cells) with natural ageing, and this is accelerated in the absence of telomerase (in |

|

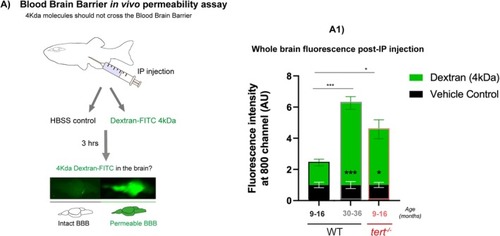

Telomerase depletion is associated with increased BBB permeability with ageing in the zebrafish brain. (A) Schematic figure of the BBB permeability assay. Dextran‐FITC 4 kDa or vehicle control (HBSS) were injected by intraperitoneal injection. 3 h later the brains were dissected and imaged in the Odyssey CLx (Li‐cor) to confirm the presence of Dextran‐FITC. Quantification of the green fluorescence in the fish brains shows higher FITC expression in old WT (> 30 months) compared to middle aged ones (9–16 months). This increased presence of dextran‐FITC in |

|

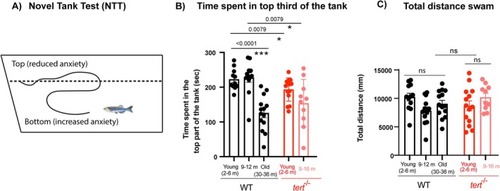

Telomerase depletion accelerates ageing‐assoicated increase in anxiety‐like behaviour. (A) Schematic figure of the setup and behaviour assessment during the novel tank test (NTT). (B) Quantifications show that old WT (30–36 months) spend less periods of time in the top part of the tank compared to younger siblings, and that this behaviour is accelerated in |

|

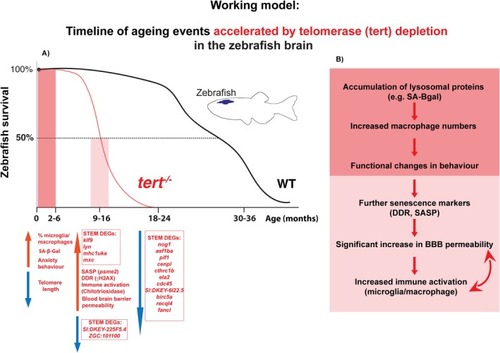

Working model: Timeline of ageing events accelerated by telomerase depletion in the zebrafish brain. (A) Survival curve showing the early to late stages of ageing in WT fish compared to |